September 2018

An interview with Susan Moore of Apollo Magazine. The article, apart from featuring contemporary and kinetic art, brings the value of ‘excluded’ artists to the attention of the art establishment, and the work of the charity Outside In in achieving this.

Rose Knox-Peebles keeps her collection of outsider art in a house as unusual and arresting as some of the works. She explains to Apollo why what she calls ‘excluded’ art is so engaging.

By Susan Moore

Photography by Kate Peters

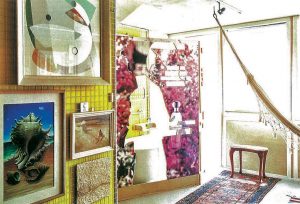

Rose Knox-Peebles divides her art collection into two categories. What she calls her ‘quiet pictures’, form a very private collection of mostly modern and contemporary British art. Her ‘noisy pictures’ include what she chooses not to call outsider art. The latter are housed in an audacious sliver of glass, steel and concrete: a contemporary beach house on a challengingly narrow site built to her specifications around this exuberant and ever-expanding gathering.

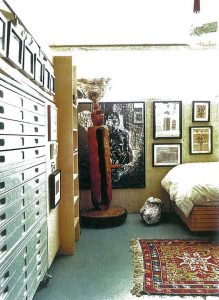

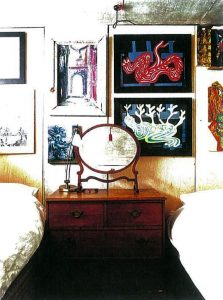

It is an assemblage as idiosyncratic as it is eclectic. Where there are no demarcations or rules. ‘Outside’ nudges ‘In’, old mingles with new, and big-name artists find no more favour than those the art world has long forgotten. In addition to paintings, drawings and prints, there is also kinetic art, sculpture and light pieces. A resistance to pigeonholing art, and artists, is perhaps an unsurprising quality in this collector. Rose Knox-Peebles is a novelist who, at 76, is equally at ease modelling, acting, and performing in music and fashion videos.

It seems that both the collection and the house are expressions of her personality. The house even resembles the collector herself: tall and slender, its most striking feature is a dramatic, pale, straight staircase that soars up the entire height of the house, in what seems like an echo of Knox-Peebles’ waist-length silver hair. It is entirely characteristic that she should think of piercing its treads with a shipping forecast cut in Morse code (Fig. 3). Rather like the prose of her novels – written under the name of Mary Telford – the bare bones of this house are spare, cool and detached; yet she has chosen to flesh them out with all manner of creative energy and emotion. This may be a minimalist house architecturally, but Rose Knox-Peebles and her husband Brian are maximalists.

Every surface of every room is lined with works of art, including the outside and inside of all the doors and cupboards. Practical wire-racking is ubiquitous, its neat grids criss-crossing walls and ingeniously morphing into museum-stack sliding doors and opening vitrines. Art even spills into the laundry room (most appropriately in the case of Wilma Johnson’s yellow rubber gloves), colonises bathroom ceilings and snakes out in the form of a Diane Maclean light-piece on to the shingle-topped flat roof. It is aurally as well as visually noisy. As you walk through the door and pass into the lobby, a motorised wood and metal spinning piece, the first of several kinetic works by Tim Lewis, clacks into action. From the left comes the sound of water, an installation by William Pye that uses an air core to propel water to rise in a vortex and then empty. An ethereal, disembodied voice singing Schubert’s Ave Maria emanates from a video piece by Cheng Ran and Cyril Duval in the downstairs loo.

‘All this has been a life-long addiction, but it is better than gin or gambling,’ Knox-Peebles says as we sit with mugs of lapsang souchong. Most works, she assures me, were and are still bought in instalments. ‘My very first paintings were bought in 1964. I was sitting at home in our little village in Kent when there was a news item on the radio about an exhibition of the Australian artist Arthur Boyd at Gallery One in London.’ She continues: ‘I don’t know why – and I had never done anything like this before – but I got a train from the village, changed at Tunbridge Wells and went to London. Needless to say the show was over. Instead there was an exhibition of this artist called David Oxtoby, and I came back with two.’

They were the first of many, for Oxtoby – who was just as admired in the ’60s as his Bradford and RA contemporary David Hockney – is one of a handful of artists who is collected in depth here. As Knox-Peebles explains, ‘Once you know an artist, faute de mieux, they will need help from time to time and you want to do something.’ Oxtoby’s work dominates the sitting room, from those two initial acrylics, The Bee and Cat (both 1964), to the more typical Pop paintings of his musical idols, which are as much vivid evocations of the energy and excitement of the music as of the performers. Elvis is king, in every sense, and he is obviously a shared passion, for Brian later points out a row of photographs of his wife embracing the star in Las Vegas. Knox-Peebles adds: ‘Dave is an extraordinary person. He gave up on galleries years ago, so few people have heard of him now. He has at last got a gallery, but he won’t sell anything.’ She opens the wire doors behind The Bee and Cat to reveal more paintings and works on paper. ‘Dave happened to be in the US at the time of Selma, and he made these extraordinary drawings too. He is so versatile, and witty.’ To prove the point, upstairs are his illustrations to Apollinaire and downstairs is a piece called Stand by Me (Fig. 5), a chair with a back-rest bearing a painting of B.B. King, which would break if anyone were to sit on it.

Many of Knox-Peebles’ early acquisitions came from the dealers Victor Musgrave (‘quite a character’), and Monika Kinley. ‘I got into outsider or excluded art through Gallery One, too. Victor showed a lot of avant-garde student art, and he also showed Scottie Wilson, who was the doyen of outsider art. His works are obsessive. I started collecting a lot of his work then, also from the Circle Gallery, but I had no idea that it was outsider art.’

A Glaswegian who left school at the age of eight, Wilson emigrated to Canada after the First World War, where he ran a second-hand shop. It was not until he was 44 that he picked up one of the pens that he was selling and began to draw. As he once explained: ‘I’m listening to classical music one day – Mendelssohn – when all of a sudden I dipped the bulldog pen into a bottle of ink and started drawing … the pen seemed to make me draw, and then images, the faces and designs just flowed out. I couldn’t stop – I’ve never stopped since that day.’ Wilson was collected by artists such as Picasso and Klee, but wary of dealers. He is represented here by painted plates commissioned by Royal Worcester and a silk scarf designed for Zika Ascher, as well as drawings and paintings.

Another early discovery was ‘a very different kind of artist. A road mender who wished he was a cowboy and called himself John Sundance King. He painted what we call the babes’ – voluptuously naïve nudes and bathers in oil on board that now grace bedrooms and bathrooms. A third was Christopher Sturgess-Lief. ‘Then there was a kind of hiatus in this part of the collection,’ Knox-Peebles explains. It was not until Pallant House Gallery in Sussex approached her to borrow the Scottie Wilsons for an exhibition in 2009 that she re-engaged with outsider art and became involved with the gallery’s Outside In initiative, which offers a platform for artists who struggle to gain entry into the art world due to ill-health, disability, isolation or social circumstance. These days she serves as a trustee: ‘I am not quite sure what I am doing there. I think I stand for the woman in the street.

‘One room here is entirely filled with art by excluded artists while the rest is all dotted about and mixed up, which is how it should be.’ Then her calm and measured voice begins to rise. ‘The thing about these artists is they are excluded. I don’t think they should be and I think their work should be hung in exhibitions alongside that of other artists. I get very angry about the fact that they get put in a box and shoved to one side. There shouldn’t be this separation. They are not using art as therapy, they are artists, full stop. I feel quite strongly about this.’

She resumes, equilibrium regained: ‘I just love this kind of work because it is so unmediated. The mainstream modern British art is highly mediated. These artists are very thoughtful and take their time and don’t dash things off unless they are sketches, and I love what they achieve after all that meticulous thought.’ She pauses, before continuing. ‘Some excluded artists achieve something comparable without aiming for it, and have a natural sense of colour, line and balance. There is nothing to say that it has to look bonkers, and I don’t like it when people suggest that these artists are not allowed to be skilful or have a technique because sometimes they do – they are no less an excluded artist because they are able to draw exquisitely or paint beautifully.

‘Their work has a quality that is different from that of practised artists, which is hard to define. They may never be able to equal the kind of painting that comes from patient hours of building up layer after layer of paint but what they often have instead is a directness and an emotional engagement. There is nothing between you and the artist. You can feel what they felt when they were painting it. You don’t stand in front of one for hours analysing it as you might in front of a Poussin or Titian, or even a Vaughan: it is there at once for you. As I walk around the house, I sometimes look at them and sometimes I don’t, but when I do, I am immediately affected by them. It seems to me that the artists are expressing something important about themselves which you might not pick up if you just met them.’

Knox-Peebles cites as an example the work of one creator of obsessively detailed pen and ink drawings. ‘He was sitting over there on the sofa one day and I mentioned that I had given up taking tablets for migraine or whatever it was, and he said: “So have I. I am a psychopath.” His drawings are very controlled, icily controlled in fact, and there is a sense of danger. I suppose there should be danger in the work of someone with such a personality disorder […] but you cannot avoid the fact that his drawings are good. With a trained eye, you can see that.’

Some artists also make the transition from outsider to mainstream. One such is the self-taught Chris Mason: ‘He was a carpenter but now he is extremely successful and definitely not excluded.’ Mason collaborates with his partner under the name Hipkiss. His large-scale work You and I Against, executed in pencil and silver ink, hangs above the staircase, and rows of his drawings are printed on the bedroom blinds.

Of all the many ‘excluded’ artists here, none takes a deeper bow than Ben Wilson, otherwise and perhaps misleadingly known as ‘The Chewing-Gum Man’. Indeed, one of his chewing-gum pieces greets visitors at the front door – a miniature painting of Rose as a mermaid with a lamp luring a sailor to his doom. An activist with a distaste for industrial waste and detritus, he had set about improving the urban environment by transforming the abandoned into the beautiful. After finding himself in trouble for ‘defacing’ other people’s property, he turned to painting on flattened gum, squashed drink cans and even cigarette stubs, which contravened no byelaws.

Yet Wilson began as a wood-carver, carving sculptures in wooded areas and making pieces from found wood. En route to the United States to execute a woodland commission, he took his tools as carry-on luggage and found himself clapped in manacles. In his oil pastels on paper, Capture I and Capture II, he presents himself as a kind of Green Man with oak-branch limbs trapped in bars (Fig. 6). While working on a piece for a wood in Finland, Wilson fell in love with a local girl and could not bear to leave. When he finally returned to the UK, he produced the dense, and minutely detailed pen and ink Finnish Narrative. Knox-Peebles explains: ‘The only material he had were these long thin strips of paper and he used them to draw the story of his love for this Finnish woman. Isn’t it wonderful? It is heart-breaking really.’

There is much fine draughtsmanship in evidence here, some of it by sculptors – Knox-Peebles has a particular penchant for sculptors’ drawings. Other works are what she describes as ‘strange pencil drawings that don’t mean anything to anybody else’. Some, like Phil Baird’s gel-pen drawing Central Tree/Spinning Hats (2010), seem to come out of the English visionary tradition of Samuel Palmer (Fig. 6). Pat Mear’s extraordinarily sure line drawings executed on coloured sheets of paper from small spiral-bound notebooks she found at Woolworths echo the experiments and fantasies of Surrealist automatic writing and drawing. ‘My idea was to draw more quickly than I could think,’ Mear has been quoted as saying. A row of her drawings span the balustrade of a wall-to-wall bunk bed (Fig. x), alongside several of Aradne’s colourful but emotionally dark woven figurative compositions, the faces of which remind Knox-Peebles of Mexican Day of the Dead skulls.

The surreal and the visionary loom large here, a thread that connects these works to Knox-Peebles’ strong holdings of English Surrealist painting as well as to the work of mainstream contemporary artists such as Ana Maria Pacheco. (Incidentally, a great number of the artists in the collection are women.) For all the noise and colour, there is also a brooding darkness and strangeness, not least in subjects of metamorphosis, which have an echo in Mary Telford’s fable-like short stories.

Knox-Peebles is, unsurprisingly, unable to resist words in, or on, works of art. This may take the form of inscriptions or attached letters, or words that are part of the composition (as in a linocut piece by Danielle Hodson; (Fig. 4) or the artwork itself. She bought a piece by Valerie Potter for its inscription, ‘I am here and I am alive you bastard’, and rejoices in the words of Chris Kenny’s twig, pin and text piece, I fear the winey-dark intimacies of love, and the wit of Carolyn Trant’s fish-shaped artist’s-book, My Mackerel Lover. She is also mesmerised by Carlo Keshishian’s obsessive painted or drawn word ‘diaries’ that look like weather fronts, and by Hipkiss’s take on a family tree.

There are words as symbols, as in Morse code, and absent words, as in the Angus Fairhurst screen around the bath, Seven pages from a magazine, body and text removed (Fig. 2). Knox-Peebles describes Fairhurst as her only YBA, and he is represented in a variety of orthodox and unorthodox media, from the mirrored cardboard of his endlessly reflected banana-skin piece to the papier-mâché and bin-bag Laocoön. Both works are in the hall (Fig. 5), as is Unwritten (2003), a mixed-media piece included in Fairhurst’s final exhibition in 2008, which, the artist told the collector, represents a man being devoured by a tree. On the day of the show’s closing, the artist was found dead, having committed suicide.

Knox-Peebles combines challenging pieces with the upbeat, and even the jauntily nautical (the presence of the sea is inescapable here). Both parts of the collection are still growing ‘but new acquisitions have to be small,’ the collector insists. ‘There is just no more space.’

Susan Moore is associate editor of Apollo.